Treatment of glaucoma in children (juvenile glaucoma)

The treatment of glaucoma in children (juvenile glaucoma) – congenital glaucoma and childhood glaucoma

Childhood or juvenile glaucoma

Glaucoma in children is a rare disease that can occur on one or both sides. In contrast to glaucoma in adults, which is one of the most common causes of blindness worldwide, childhood glaucoma is rare.

They can be divided into different categories depending on their occurrence and cause.

Recently, an international panel of experts published an updated classification for childhood glaucoma. This classification distinguishes between two types:

- Congenital glaucoma: present from birth

- Infantile glaucoma: glaucoma that develops, for example, after cataract surgery in childhood (cataract)

There are also childhood glaucomas that are associated with physical or eye-related malformations. Childhood glaucoma can also develop as a result of acquired diseases such as chronic inflammation of the choroid (uveitis) or after accidents.

Finally, there is juvenile open-angle glaucoma, which corresponds to glaucoma in adolescence without accompanying malformations or underlying diseases.

While glaucoma is relatively common in adults in the normal European population, affecting around 1.4-2.0% of the population, it is a rare disease in children.

In countries such as England, around 5 in 100,000 newborns are affected by childhood glaucoma. Often both eyes are affected and overall cases of infantile glaucoma are relatively rare.

The small number of patients affected makes it difficult to research the causes and evaluate the effectiveness and safety of treatment strategies. This makes the disease a challenge in the field of medical research and care of children with glaucoma.

Secondary childhood glaucoma and its characteristics

Congenital glaucoma is a rare disease that manifests itself in increased eye pressure at birth and affects around 100 new cases per year in Germany. This disease is due to a maldevelopment of the trabecular meshwork, whereby membranous structures, also known as Barkan membranes, block the chamber angle and restrict the outflow of aqueous humour.

This leads to an increase in intraocular pressure. As the eye tissues in young children are still elastic, the high pressure results in an enlargement of the eye, also known as buphthalmos or “bull’s eye”.

Despite their rarity, congenital glaucomas are responsible for around 5% of childhood blindness. As a rule, it is a sporadically occurring disease without familial clustering (recessive inheritance). In contrast, childhood glaucomas associated with other malformations or syndromic diseases are often inherited dominantly.

Symptoms and effects of congenital glaucoma

The main characteristic of congenital glaucoma is the enlargement of the eyeball due to high intraocular pressure. If the disease affects both eyes, this can initially be misinterpreted as “big, beautiful eyes”.

The dilation of the eye leads to corneal opacities and an increase in short-sightedness. Children with congenital glaucoma also show sensitivity to light, increased tearing and tend to pinch their eyelids shut frequently.

The deterioration of visual function in children with glaucoma results on the one hand from damage to the optic nerve due to increased intraocular pressure and on the other hand from the high risk of developing amblyopia.

Amblyopia is a form of amblyopia that occurs when the eye cannot learn to see properly. At birth, infants can only perceive blurred images and vision is a learning process in which the eye is linked to the brain.

However, if sensory stimuli are missing, whether due to corneal opacity, high myopia or a significant difference between the eyes, the nerve connections cannot be properly formed. This leads to the eye having poor vision later on, even if the eye structures are intact.

Childhood glaucoma and its characteristics

Apart from primary congenital glaucoma, there are also cases of increased intraocular pressure in children that occur due to other eye diseases. The group of glaucomas following cataract surgery in children is particularly important.

If a lens opacity occurs in children, rapid surgery is required to prevent the development of amblyopia (amblyopia). However, it remains unclear why some of these children often develop eye pressure elevations that are difficult to control years later.

The challenges in therapy are generally greater when malformations are present and the prognosis for visual development is less favourable.

Signs of childhood glaucoma: symptoms from the parents’ perspective

The symptoms of congenital glaucoma can be difficult to recognise in newborns, babies and young children as they are not yet able to communicate their symptoms. It is therefore of the utmost importance that parents pay particular attention to changes in their children and seek medical advice immediately if they notice any abnormalities.

The following symptoms could indicate congenital glaucoma:

- Sensitivity to light (photophobia): If your baby reacts strongly to light and shows signs of photophobia, this may indicate an eye problem.

- Watery eyes (epiphora): If your child’s eyes water frequently for no apparent reason, this is another symptom to be aware of.

- Turning away from light: Observe whether your child turns their face away from light or tries to avoid bright light.

- Rubbing the eyes: Frequent rubbing of the eyes can be an indication that something is wrong with the eyes.

- Noticeably large eyes: If your child has excessively large or “beautiful” eyes, this could indicate an enlargement of the eye due to increased intraocular pressure.Excessive crying: Increased crying or restlessness from your child may indicate eye problems.

- Suspicion of increased intraocular pressure: If your ophthalmologist suspects increased intraocular pressure, you should take this seriously.

- Grey or cloudy cornea: If you have the impression that the cornea in your child’s eyes looks grey or cloudy, this may indicate a possible clouding of the eyes.

- Eyelid spasm (blepharospasm): The child often closes the eyelids in a spasmodic manner

The signs of infantile glaucoma usually affect both eyes, but often not to the same extent. Children over the age of three with infantile glaucoma often develop progressive short-sightedness (myopia).

Without treatment, there is a risk of blindness as the optic nerve becomes increasingly damaged.

In the case of juvenile glaucoma, there are usually no symptoms at first. The increased intraocular pressure is often discovered by doctors by chance during routine examinations. If juvenile glaucoma progresses, vision can be significantly impaired.

Those affected often experience limited vision in the visual field. They can still recognise objects and people in the centre of their field of vision, but can no longer see things on the periphery. This can be noticeable in everyday situations such as climbing stairs or in road traffic.

Symptom of buphthalmos in infants

An excessively large eyeball can be a sign of congenital glaucoma, as chronically increased eye pressure can lead to an enlargement of the eyeball due to the soft and elastic tissue during foetal development or in infancy.

If you notice particularly large eyes in a newborn, you should consult an ophthalmologist immediately, as this could indicate possible glaucoma. In older children (from the age of 2 to 3), this enlargement of the eyeball no longer occurs as the tissue becomes firmer.

Childhood glaucoma: challenges in diagnosis and examinations

The diagnosis of childhood glaucoma requires specific examinations that vary depending on the age of the young patient. In general, these examinations include a comprehensive eye examination focussing on the chamber angle examination, eye pressure measurement, optic nerve examination and visual field examination.

In addition, it is important to determine the refractive power of the eye in order to recognise signs of enlargement of the eye, such as an increase in short-sightedness. Furthermore, a comprehensive paediatric examination is required to exclude or diagnose possible underlying diseases or malformations.

For infants and newborns who cannot be examined while awake, an anaesthetic examination may be necessary. This requires a specialised paediatric intensive care unit. If glaucoma is suspected, these examinations may need to be repeated, often under anaesthesia for urgent procedures.

The diagnosis of paediatric glaucoma requires a careful examination involving various procedures and measurements. The main methods of diagnosis are

- Measurement of the diameter of the cornea: both vertical and horizontal).

- Pachymetry: A measurement of the thickness of the cornea.

- Tonometry: A method of measuring intraocular pressure, although this can be prone to error in babies and young children, both awake and anaesthetised. In awake children, rebound tonometry can be a short and painless alternative that does not require anaesthetic eye drops. There are also other tonometry methods, such as applanation tonometry, which is often performed at the beginning of anaesthesia.

- Ophthalmoscopy (ophthalmoscopy or fundoscopy): Ophthalmologists use a special instrument, the ophthalmoscope, which greatly magnifies the eye and allows them to carefully examine all eye structures and changes. Particular attention is paid to the optic disc.

- Ultrasound examination (sonography): This method measures the length of the eyeballs and is suitable for both diagnosis and follow-up.

- Gonioscopy: This technique can be used to examine the chamber angle. A special contact lens called a gonioscope is used. Depending on the examination method – direct or indirect – different types of contact lenses are used.

- Visual field measurement (perimetry): This is carried out on older children.

In families with an increased risk of congenital glaucoma, prenatal diagnostics can also be considered. This type of diagnosis aims to determine the risk of the disease, especially if there are known mutations in the family that lead to congenital glaucoma.

Genetic counselling can also be useful to better understand the risk of developing the disease. However, it should be noted that genetic factors do not play a role in all those affected, as the disease can also occur sporadically.

Juvenile glaucoma is diagnosed in a similar way to congenital glaucoma, although the examinations are often easier to carry out in older children. In addition, an eye test is carried out in order to obtain indications of short-sightedness, and from school age, a restriction of the visual field can often also be detected.

In many cases, juvenile glaucoma is inherited, so genetic counselling for family members can be helpful to better understand the risk of developing the disease. Human geneticists can assist in determining the risk of disease for family members.

Typical findings in congenital glaucoma are increased eye pressure of more than 21 mmHg, an increase in myopia due to eye enlargement, corneal opacities and a corneal diameter of more than 11 mm in newborns as well as damage to the optic nerve with an enlarged excavation (hollowing out of the optic nerve).

In the past, numerous anaesthetic examinations were required to carry out eye pressure measurements after operations or as check-ups. There are now new technologies for measuring pressure, such as rebound tonometry or the ICare Tonometer®, which in many cases also allow pressure to be measured in awake infants.

A close connection to an orthoptic department (visual school) is of great importance in order to monitor visual development and changes in the refractive power of the eyes and correct them accordingly.

In older children and adolescents, imaging procedures such as optical coherence tomography (OCT) or confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (Heidelberg Retina Tomograph®) are also used.

However, it should be noted that there are no special comparative databases for children. Measuring eye pressure in children poses a particular challenge, as incorrectly high values often occur due to pinching. The precise interpretation of the findings by the ophthalmologist is therefore of great importance.

Causes of congenital glaucoma

The prevalence of congenital glaucoma in Germany is around 1:15,000. Most cases are primary glaucoma, which means that the glaucoma is either congenital or first appears in childhood and has no recognisable concomitant diseases or causes.

The exact causes of congenital glaucoma are not yet fully understood. It is assumed that shortly before or after birth, certain eye structures, in particular the angle of the chamber and the trabecular meshwork, are not sufficiently mature.

As a result, the aqueous humour, the clear fluid in the eye, cannot drain properly between the iris (iris) and the cornea (cornea) in the trabecular meshwork.

The trabecular meshwork is a loose tissue that serves as the main drainage pathway for the aqueous humour in the eye and resembles a sponge under the microscope. Although the production of aqueous humour is normal, the intraocular pressure rises if the outflow is obstructed.

Causes of childhood glaucoma: Juvenile glaucoma

The causes of juvenile glaucoma are similar to those of the congenital variant. There is a disturbance in the outflow of the aqueous humour through the trabecular meshwork into Schlemm’s canal, the outflow channel in the eye.

However, the increased intraocular pressure in juvenile glaucoma only occurs at a later stage. It is assumed that the chamber angle and the trabecular meshwork are more mature, which means that the increased intraocular pressure only becomes noticeable later in life.

This pattern is probably similar in infantile glaucoma. As the drainage system is partially mature, the intraocular pressure may still be within the normal range in the first years of life. The pressure then gradually increases during childhood.

Juvenile glaucoma often shows a hereditary predisposition and doctors have identified mutations in the CYP1B1 and MYOC genes as possible causes.

Treatment of childhood glaucoma

The treatment of congenital glaucoma is primarily surgical. The main aim is to open the abnormal trabecular meshwork to allow the aqueous humour to drain. This is traditionally achieved through a trabeculotomy.

In this procedure, Schlemm’s canal is localised using a fine metal probe and the trabecular meshwork is torn towards the inside of the eye. In recent years, the 360° trabeculotomy with a special illuminated probe, in which the trabecular meshwork is opened over the entire angle of the chamber, has become increasingly popular.

If the reduction in intraocular pressure is not sufficient after this operation, further surgical procedures such as trabeculectomy (a classic glaucoma operation) or interventions with implantable devices can be considered.

However, there is an increased risk of scarring in children, which can affect the success of the operation. Another option is cyclophotocoagulation, in which the ciliary body, which is responsible for the production of aqueous humour, is sclerosed.

The chances of success are highest with the first operation and decrease if further follow-up operations are required. Overall, it is estimated that the intraocular pressure is regulated in around 75% of small patients after 10 years, regardless of the number of operations.

If pressure-lowering surgery alone is not sufficient, pressure-lowering eye drops can also be used. In young children, prostaglandin preparations such as latanoprost and travoprost are the only approved options, although their pressure-lowering effect may be less in children than in adults.

The long-standing beta-blocker timolol should be used in children in special low doses and only after the paediatrician has ruled out heart or lung disease.

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors such as dorzolamide and brinzolamide are suspected of damaging the endothelium of the cornea and should be used sparingly.

The active ingredient brimonidine is strictly contraindicated as it can cause serious respiratory problems. Pilocarpine is also only used in children in exceptional cases.

An essential component of the therapy is the treatment of refractive errors (glasses) and amblyopia (weak vision). The spectacle values and visual function must be monitored regularly in close co-operation with an orthoptics department/vision school.

Depending on the findings, amblyopia is treated with occlusion therapy, in which the stronger eye is covered to strengthen the weaker eye.

If there is secondary childhood glaucoma due to another underlying condition, treatment will depend on the cause or associated condition. The therapy can be complex and requires intensive care and individualised treatment approaches.

In addition to medical treatment, early support for young patients is necessary to enable the best possible development. The Bundesverband Glaukom-Selbsthilfe is an important point of contact for parents and families, providing important information and support.

Surgical methods for the treatment of childhood glaucoma

In contrast to glaucoma in adults, the surgical correction of congenital and childhood glaucoma is extremely effective and has a high success rate. The most commonly used method is trabeculotomy or probe trabeculotomy.

Probe trabeculotomy – creating the drainage pathway

The operation to treat glaucoma aims to correct the disturbed outflow system in the eye. During probe trabeculotomy, the Schlemm’s canal is probed and opened, which is done over a limited section.

This procedure enables improved drainage of the aqueous humour and leads to normalisation of the intraocular pressure. Occasionally, there may be reflux of blood into the anterior chamber of the eye, which is usually an indication of the success of the operation and normally resolves quickly.

360 degree trabeculotomy – Comprehensive drainage improvement

In 360 degree trabeculotomy, the Schlemm’s canal is first dilated with a catheter and then opened along its entire circumference.

Some blood in the eye in the first few days after the procedure is also considered a sign of a successful outcome.

Controlled cyclophotocoagulation – reduction of aqueous humour production

In some cases, controlled cyclophotocoagulation may be necessary at a later stage. This involves the targeted application of heat (laser coagulation) to a part of the ciliary body that is responsible for the production of aqueous humour.

This leads to a reduction in aqueous humour production and thus to a long-term drop in intraocular pressure. This treatment can be repeated several times if necessary.

Cold treatment of the ciliary body (cyclocryocoagulation) – stabilisation of intraocular pressure

For secondary glaucomas that occur due to eye inflammation, for example, cold treatment of the ciliary body can help to stabilise the intraocular pressure.

During this procedure, a specific part of the ciliary body is treated with a temperature of -80 degrees Celsius, which reduces the production of aqueous humour. Temporary swelling of the conjunctiva after the operation is not normally a cause for concern.

Progression and outlook for congenital and juvenile glaucoma

The course and prognosis of congenital and juvenile glaucoma vary from individual to individual and are difficult to determine in advance. They are highly dependent on the time at which the eye disease is diagnosed and treated.

Starting treatment early leads to better prospects. If glaucoma is recognised and treated early, the optic nerve has not yet suffered irreparable damage, vision can be preserved and blindness can be avoided.

Most patients who have been successfully treated for glaucoma in childhood go on to have stable intraocular pressure, a healthy optic nerve and no restrictions in the visual field.

The prognosis for juvenile glaucoma is generally more favourable if the diagnosis is made early and the eye disease is treated in good time.

Modern treatment options for juvenile glaucoma at Eye Acupuncture Noll

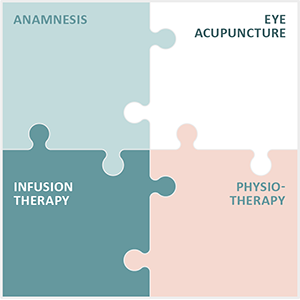

Eye Acupuncture Noll specialises in the treatment of chronic and degenerative eye diseases, including juvenile glaucoma. The Integrated Eye Therapy according to Noll developed by Michaela Noll consists of four core elements:

- A thorough medical history to obtain a complete picture of the patient’s state of health.

- Eye acupuncture according to Prof Boel, which is specially tailored to the needs of our young patients.

- Customised infusions that are specifically tailored to the patient’s specific conditions.

- Customised physiotherapy that supports the general treatment.

For over 13 years, our practice has built up an international patient base and we are particularly proud of the positive feedback we receive from our patients after their treatments.

Juvenile glaucoma is a rare disease that requires special attention. Compared to glaucoma in adults, which is a common cause of blindness worldwide, glaucoma in children requires a different approach and treatment strategy.

Our specialised therapy is designed to meet the individual needs of our young patients and significantly improve their quality of life. Even though treatment can be difficult, our aim is to achieve optimal results without making overly optimistic promises.

Please note that the success of treatment depends on various factors and that regular check-ups are necessary. We are committed to developing and adapting the best possible treatment plan for each child.